New AIC paper appears to cherry-pick data to fit “gendered violence” narrative

Last month the Australian Institute of Criminology (AIC) released a research paper titled Domestic violence offenders, prior offending and reoffending in Australia, by Shann Hulme, Anthony Morgan and Hayley Boxall.

As Joe Hildebrand pointed out in his op-ed for news.com.au ‘Deadliest of lies' we keep swallowing, the paper found,

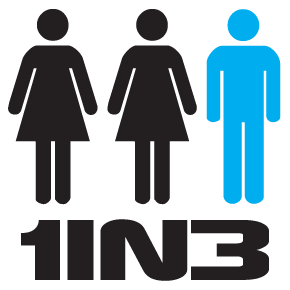

there was a massive concentration of domestic violence in disadvantaged and indigenous communities and that alcohol was also a driving factor. Perhaps most significantly, despite the prevailing narrative that domestic violence is a simple male versus female issue, it found that in fact it was a tiny minority of men who were responsible for a vastly disproportionate amount of abuse.

While it is exciting to see more overwhelming evidence pointing to the actual causes and risk factors for domestic violence, rather than the “gender inequality” narrative that has been trotted out by successive governments for decades, the AIC paper makes some serious errors when it comes to female perpetrators of domestic violence.

The AIC paper claims,

there was evidence that the circumstances of female perpetrated violence and male perpetrated violence were different. Specifically, incidents and relationships in which women were perpetrators of domestic violence frequently involved bi-directional violence, meaning they were often victims of violence as well.

As evidence to support this claim the AIC cites a 2007 paper by Mouzos and Smith. This source paper found that incidents and relationships in which men were perpetrators of domestic violence also frequently involved bi-directional violence, making a lie of the AIC’s claim:

Two-thirds of the male detainees (66%) and around three-quarters of the female detainees (74%) reported being both victims and perpetrators of partner violence.

The source paper also found, “a statistically significant higher percentage of females also reported perpetrating intimate partner violence (IPV) during the past 12 months than male detainees (47% compared to 38%).” This included acts of severe violence such as “used a knife or gun on your partner” (8% of female perpetrators vs 1% of male perpetrators) and “beat up your partner” (10% of female perpetrators vs 3% of male perpetrators). Strangely there was no mention of this by the AIC, despite it being important evidence that would have supported their claim that the circumstances of female perpetrated violence and male perpetrated violence were different.

The AIC paper also uses the fact that where women are the respondents to a protection order there are often mutual orders in place, to argue that women who use violence often do so from the position of victimhood (but men do not).

There is another, more obvious, reason for this gender imbalance in protection orders. Most international peer-reviewed research on domestic violence (including research cited by the AIC paper) finds that the majority of domestic violence is bidirectional, with a minority either unilaterally male-perpetrated or female-perpetrated.

Women are more likely to take out protection orders against men than men are against women. There are a number of reasons for this. Male victims of domestic violence are more reluctant than female victims to seek any help whatsoever. They are less likely to have told anybody, they are less likely to have sought advice or support, and they are less likely to have contacted police about experiencing partner violence.

Many barriers to male victims disclosing their abuse are created or amplified by the lack of public acknowledgement that males can also be victims of family violence, the lack of appropriate services for male victims and their children, and the lack of appropriate help available for male victims from existing services… “Where do I seek help? How do I seek help? Where can I escape to? Will I be believed or understood? Will my experiences be minimised, or will I be blamed for my own abuse? Will services be able to offer me appropriate help? Will I be falsely arrested because of my gender? Will my children be left unprotected from the abuser?”

Many male victims face barriers to disclosing their abuse because of the challenges such disclosure brings to their sense of manhood… Shame, embarrassment, social stigma. Feeling ashamed because they are unable to protect themselves. Fearing being laughed at or ridiculed or being called ‘weak’ or ‘wimpy.’ Disbelief. Denial. Making excuses for the perpetrator’s behaviour.

This imbalance in help-seeking combined with the frequency of bilateral domestic violence, creates the imbalance where female perpetrators are more likely to have mutual orders in place than are male perpetrators. It very likely has little to do with female perpetrators being more likely to also be victims than male perpetrators.

Lastly the AIC paper claims,

there are important differences between male and female offenders in the circumstances and drivers of domestic violence. In particular, women are more likely to use violence in self-defence or in response to historical violence perpetrated by their partner.

As evidence to support this claim the AIC cites a 2018 paper by Mackay et al. The actual findings from this source paper were quite equivocal. When it comes to using violence in self-defence, it found that while some studies had found a significant difference between men's and women's endorsement of self-defence as a motivation, othershad found no difference. The authors also note in one study where women’s use of violence in self-defence was high (65.4%), it was still as high as 50% for men.

When it comes to women using violence in retaliation to violence perpetrated by their partner, the source paper found that retaliation is clearly a motivation for a proportion of both male and female perpetrators of IPV. Once again, rather than supporting the AIC’s claims, the cited evidence finds them to be erroneous.

Interestingly when it came to the use of IPV as a means of achieving control or for some instrumental gain, the source paper found that,

for some women, gaining control over their partners using IPV, is indeed a motivation for its perpetration. Whilst it might be expected that this explanation for IPV would be more prevalent in men, the evidence suggests that women and men are both as likely to describe their motivation for perpetrating IPV as one linked to control.

Once again there was no mention of this by the AIC, despite it directly challenging their claim that there are important differences between male and female offenders in the circumstances and drivers of domestic violence.

Regretfully it appears the AIC has dropped its usually high research standards in order to fit into the prevalent but erroneous “gendered violence” narrative. We look forward to the day when their research returns to being based upon the cited evidence, regardless of whether it fits the prevailing narrative or not.