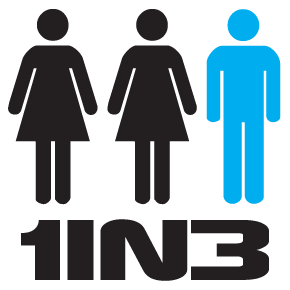

One in Three response to the proposed NSW Domestic Violence reforms

The proposed new NSW Domestic Violence Framework is largely the same old story when it comes to ignoring the plight of male victims of family violence and abuse. We would strongly urge readers who wish to comment upon the proposed Framework to do so at engage.haveyoursay.nsw.gov.au/it-stops-here. The deadline for comments is 5pm on Tuesday 30th July 2013.

For those who would like to see the One in Three Campaign's comments, they are provided for you below. Please feel free to base your own submission upon any of these.

1. What do you think are the critical elements of the strategies and actions for prevention to drive change?

A new focus on effective and evidence-based prevention and a prevention-focused funding program (as long as both male and female perpetrators receive support and attention).

An electronic, common risk identification tool.

Central referral points to make the path easier for victims seeking support from the system (as long as these are available to both male and female victims).

New information sharing arrangements to help agencies work together for victim safety .

Implementation of Safety Action Meetings to monitor and assess victims at serious threat.

Programs that hold perpetrators to account for their actions and support them to stop using violence (as long as they are available to both male and female perpetrators).

A new approach to investing in research and building evidence to support our activities and investments (as long as this research is un-gender-biased scientific research rather than feminist advocacy research that only studies female victims and male perpetrators).

Children experiencing violence are supported and inter-generational violence is averted (as long as this includes violence by both men and women).

2. What do you think must be done to prevent the intergenerational transfer of violence?

The largest and most recent Australian survey of young people and domestic violence (National Crime Prevention, 2001) found that witnessing parental domestic violence had a significant effect on young people’s attitudes and experiences. Witnessing was also the strongest predictor of subsequent perpetration by young people. The best predictor of perpetration was witnessing certain types of female to male violence, whilst the best predictor of victimisation in personal relationships was having witnessed male to female violence.

The same survey found that 14.4% of young people had witnessed physical violence perpetrated both by the male against the female and the female against the male. 9.0% reported that violence was perpetrated against their mother by her male partner but that she was not violent towards him. 7.8% reported that violence was perpetrated against their father but that he was not violent towards her. The most severe disruptions on all indicators occurred in those households where both male to female and female to male violence was reported (i.e. two-way couple violence).

If the best predictor of young people going on to perpetrate violence in their adult relationships is witnessing their mother/step-mother perpetrating violence against their father/step-father, we need strong community education and awareness programs saying no equally to ALL domestic and family violence, not just that perpetrated by males against females.

We also need respectful relationships and conflict management education programs in our schools that teach children and young people how to relate to their peers, partners, boyfriends and girlfriends in respectful, non-violent ways, whether or not they are male or female, and whether or not they are straight or gay.

If the most prevalent and damaging scenario for young people is witnessing mutual parental violence, we need programs that hold both male and female perpetrators to account for their actions and support them to stop using violence, especially when both parents are using violence.

3. How do you think the proposed reforms and the practice standards will change the 'service' a victim receives from 'the system'?

For female victims, the reforms appear set to greatly improve the ‘service’ victims receive from ‘the system’.

However, the review of the domestic and family violence service system by the NSW Parliament’s Standing Committee on Social Issues found that there are few programs for male victims of domestic violence. The proposed reforms don’t seem to do much at all to improve this situation.

The only part of the entire Framework that specifically mentions supporting male victims is:

“Strategy 1.3 Immediate referral to victim services

“All victims will be immediately referred to a local Women's Domestic Violence Court Advocacy Service (WDVCAS), by a police office that attended the event, before the end of the officer's shift.

“Where no WDVCAS is available or for male victims, victims will be referred to the Victims Access Line (VAL) who will coordinate access to local support. The VAL will facilitate support and information before court and provide support to access counselling, financial assistance and referral to local services.

“Referral arrangements will take into account the availability of local services, and new pathways that are agreed through local implementation of the NSW Domestic and Family Violence Framework.

“The purpose of the referral is to ensure that victims have information, support and advocacy to ensure they are able to participate in the legal process, their needs and safety are assessed, and they have access to support as soon as possible. Each local area command will have a referral agreement with WDVCAS or an appropriate local support service.”

The question, as always, is "what services will the VAL refer male victims on to when there are so few available?!".

4. What do you think will be critical to ensuring Safety Action Meetings are effective?

All victims and perpetrators, whether they are male or female, must be supported equally and in an unbiased manner.

5. What must be done to ensure high-risk people feel confident/comfortable about their information being shared with or without their consent at a Safety Action Meeting?

Ensuring that Safety Action Meetings are completely confidential, and that individuals and/or organisations who breach this privacy are punished appropriately.

6. What do you think the Central Referral Point must consider when dealing with people impacted by domestic and family violence to give them the confidence they will be responded to/supported?

It must believe victims’ stories unquestioningly, whether they are male or female.

It must treat male and female victims with care, respect and confidentiality.

It must be able to refer male and victims on to appropriate services (at present, very few exist for male victims).

It must acknowledge the differences between male and female victims and act appropriately (e.g. the additional barriers faced by male victims in coming forward and disclosing their situation).

7. The reforms acknowledge that an additional and/or different responses are required for victims from high risk groups (eg. Aboriginal, CALD, people with disability, people who identify as LGBTIQ). What do you think needs to be addressed or considered to enable these more effective responses?

In the case of the LGBTIQ community, programs must be established that hold both male and female perpetrators to account for their actions and support them to stop using violence.

Gay men and lesbians can be reluctant to report the abuse they are suffering because they are afraid of revealing their sexual orientation. They can also suffer threats of ‘outing’ of their sexual preference or HIV status by the perpetrator. The perpetrator might also tell them that no one will help because the police and the justice system are homophobic.

8. Strategies to suggest programs that hold perpetrators to account for their actions and support them to stop using violence. Do you think this is enough? If not, what other suggestions do you have?

Such strategies must be available for both male and female perpetrators of domestic and family violence if we are serious about breaking the cycle of violence.

What reason can the government provide for not establishing a referral service for all perpetrators of family violence and abuse, regardless of gender? Imagine establishing a referral service that arbitrarily excluded another class of people, for example, a ‘gay referral service’ (no heterosexuals allowed) or a ‘white referral service’ (no CALD people allowed) or a ‘jewish referral service’ (no other faiths allowed). Violence is violence. To not support female perpetrators of domestic and family violence (against men, other women and children) is a fundamental breach of Australia’s human rights provisions.

Such strategies must also be evidence-based with a triage system so that each perpetrator’s individual circumstances can be assessed and treated. Perpetrators whose violence stems from drug and alcohol abuse can receive appropriate treatment. Perpetrators whose violence stems from being abused or witnessing violence as a child can receive appropriate treatment. Couples who are in a mutually violent and/or abusive relationship (where both are perpetrators) can receive appropriate treatment. Perpetrators with inadequate conflict management and affect regulation skills can receive appropriate treatment. Perpetrators with unaddressed mental health issues can receive appropriate treatment.

Strategies with a ‘one size fits all’ approach such as the Duluth model (which assumes that all perpetrators use violence because of their patriarchal beliefs), may only have success with a very small percentage of perpetrators. All other perpetrators will not only fail to receive help, but will possibly ‘tune out’ or ‘switch off’ as their individual needs aren’t being met.

9. Do the reforms adequately enable the community to respond to Domestic and Family Violence as a whole?

Absolutely not. Domestic and Family Violence as a whole includes both male and female victims and perpetrators, as well as couples (both straight and gay) who use mutual violence. The current reforms only significantly assist female victims and male perpetrators.

The philosophical underpinnings of the reforms are fundamentally flawed. How they can possibly be applied to the one-third of victims of family violence that are male is anyone's guess:

“The NSW prevention strategy has been informed by the theoretical framework developed by VicHealth which draws on the socio-ecological model. The key social and economic determinants of violence against women have been categorised as:

“• Belief in rigid gender roles and/or weak support for gender equality, masculine sense of entitlement, and male dominance and control of wealth in relationships (individual factors).

“• Culturally-specific norms regarding gender and sexuality, and masculine peer and organisational cultures (community/organisational factors).

“• Institutional and cultural support for, or weak sanctions against, gender inequality and rigid gender roles (societal factors).”

10. What do you think are the key issues to consider to enable a victim to move more effectively through the service pathway?

Respecting victims’ wishes. Believing their stories. Treating them with sensitivity and respect. Communicating effectively with other services in terms of referrals and case management.

At present there simply is no service pathway available for male victims of domestic and family violence as there are so few services available to them. Such services need to be established as a matter of urgency.