1IN3 Podcast Ep.007: Intimate Partner Abuse of Men Workshop - Part 6

We feature highlights from the Intimate Partner Abuse of Men Workshop held on Wednesday 16 June 2010 in Perth, Western Australia. The workshop was aimed at service providers plus anyone who works with victims and perpetrators of family and domestic violence, and considered the implications for service providers of the Edith Cowan University (ECU) Intimate Partner Abuse of Men research.

In this, the sixth part of the workshop, Richard Wolterman from Lifeline reflects on more than 20 years of working with both male victims and perpetrators.

Richard Wolterman: Good morning everyone. I find myself in the company of great academics and unfortunately I never reached a Ph.D. because I started doing different things. That means my professional life and working in the field of domestic violence and other abuse-related areas are experiential and I will relate my experience to you as such and from the heart.

I’ve been working the field for about 20 years, from 1988 onwards, more or less. Before I give an oversight I just want to speak to the lady from Fremantle: the word “hope” struck a cord with me. I think the word “hope” is a key word that does not appear in any guidelines for treatment in particularly the domestic violence area and I think it does not necessarily apply to CALD to people or multicultural cultural victims or perpetrators. I saw it as a major point for us as counsellors and group facilitators in the first place to find ways of bringing hope to the people who came for assistance. And secondly, empathy and being with them. I hope I can talk about it later a bit.

It’s necessary for me to do some self revelation and I just want to let you know that domestic violence is a broad field but it’s also a narrow field. And I’m actually happy to say that I’ve worked in a lot of areas. It started in 1988 in New Zealand with private practice combined with avocado growing. I think it’s a remarkable, fruitful combination working out in the fields and doing counselling. But it encompassed family court counselling, victim support, at the time family court encompassed all the various aspects of separation, conciliation, reconciliation, custody access, children, anger management, and also domestic violence which started to become an issue at the time.

I also was a probation officer and a counsellor, sorry, a contractor for corrective services with violent offenders and sexual offenders the time. The Hamilton Project in New Zealand was I think the first overseas location of the Duluth Model and I became an approved and registered program developer, and also counsellor in New Zealand for male perpetrators. There’s one area in particular, spiritual abuse support that I started up and I’m still engaged with that in different ways.

Coming to Australia in 1998 when I was recruited by Anglicare to set up male domestic violence services in Albany that encompassed I suppose it was the first Australian men’s domestic violence crisis service, but also what we call the normal perpetrator group programs. And later on an early intervention family domestic violence program. Other fields were child protection and currently I’m managing a program for separated fathers with Lifeline. The last item on the list is probably more impacting on me as a professional than anything else because there is also a history of abuse that I never sought out for myself.

And I was never determined to consciously work into the abuse counselling field but two years at least of sexual abuse at the Catholic seminary has marked my life. Further exposure to a war-torn country, living in the Middle East with terrorist border crossings and bus bombings did an additional damage. A further year-in-a-half in the Persian Gulf War and a detainment by the Iranian navy was another aspect of a traumatic experience, and there were a few more. But it helps me to come to terms with victims’ issues.

There’s a few areas I’m going talk about briefly. One is definitions. I’ll talk about the programs we do and about the theoretical background for the running programs with perpetrators. At the top you see a familiar definition of domestic violence. That’s from the DVPU, the Domestic Violence Prevention Unit from 1998, and two subsequent publications on best practice model. Domestic violence is considered to be behaviour which results in physical, sexual, and/or psychological damage, forced isolation, economic depravation: all behaviour which causes the victim to live in fear.

Now when I did the programs right from the mid ’80s we always produced definitions of domestic violence and every agency had its own definition. I added here the family court. What a family law definition as we have it today, and if you read with me, it actually says, “family violence means conduct, whether actual or threatened, by a person towards a person or property of the member of the person’s family, that causes them or any other member of the person’s family reasonably to fear for - or reasonably to be apprehensive about - his or her personal wellbeing or safety.” A very interesting definition.

This particular definition indicates that from a male victim perspective we do not necessarily be living in fear but we can be reasonably apprehensive about our wellbeing or safety. As a matter of fact one of the clients I had in our groups, he was violent in the sense that he actually used a knife on his partner. While he was attending the program on a community based order and lived separately from his ex-partner, she started to stalk him, break-in, steal his car, and sent two bullies to beat him up.

And he was wondering whether he could get a VRO against her, and when he went to court he didn’t get one. He was sent home. I showed him this particular definition and - I must add, the guy couldn’t read or write unfortunately - so I underlined for him the phrases “reasonably apprehensive about his wellbeing.” He went back to court and he immediately got a VRO and that really helped him through the program. As a matter of fact, after 26 weeks I found out that he and his partner are back together and he actually came to thank me for the involvement in the program.

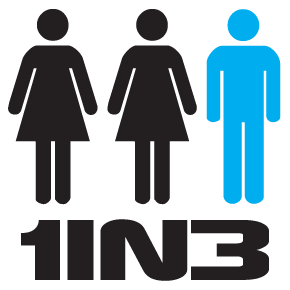

Some of the issues about male victimisation or even male help-seeking behaviour were pointed out previously but from my experience and particularly where it relates to the definitions we saw earlier, the definitions apply to both genders but may be interpreted in different ways. They do not consider the differentials between female and male victimisation or female and male perpetration. They do not consider the male and female difference in help seeking behaviours, the services’ appeal that was pointed out by Rob Donovan, the services’ access availabilities, the victimisation experiences or the victimisation reporting experiences. Perpetration behaviours are different and perpetration reporting behaviours are different. And there is a differential in societal stigmatisation.

Now I chose to write up a list of observations from my work in perpetrator programs and I hope you’ll take them home and read them and analyse them. And if there are any other group facilitators present I hope we will get some acknowledgement from others who have similar observations. What I see in the perpetrator programs and I’m speaking about court-mandated clients, paralese but also voluntarily-referred men.

I think I found the involvement in working with offenders challenging but extremely satisfying. It is the same hope that we try to bring to people who are actually lost in perpetrations, that raises our adrenaline levels when there are good - when there is good progress in the program it raises the stakes. And it doesn’t just give the facilitators a good feeling but it really helps the perpetrators to come to terms with their issues. But if there is no progress it’s also really not a good feeling.

Facilitators, I think are very special people. They are the human resources, the mediums who will help assist the men address their issues. I say that they’re undervalued. That may apply actually to other people working in the field. We need the right mix of specialist knowledge, empathy inside, inside stimulation, and capacity to engage people individually and in a group. Facilitators are forced actually to comply for the sake of agency dependancy on funding body requirements that takes away a measure of freedom.

However, we also know that know real internal change can take place by enforcement, or compliance and control. By doing that there’s really no therapeutic basis for client dignity which is an essential part of the therapeutic relationship. I also find that the program content is not that important, it’s just a vehicle that we use and as such there may be no such thing as a best practice model: a good practice model, maybe, which is current for today.

One of the critiques is that the programs may not be as successful as we wish they were. We can blame that on the perpetrators. We can blame it on the facilitators but perhaps the program itself should be redesigned. Now I’ve got a few remarks and observations about the Duluth Model as it was developed and applied. As you know there is a - basically an interagency model used in America, originally based on the patriarchal violence model. It presumes a power imbalance and male oppression. Unfortunately it claims exclusive rights, the sociopolitical rights to this truth. Now perhaps that should be challenged. But we do find it permeates now as an ally in justice, family law counselling, etcetera.

As I can see it, it forces us to apply a certain model without giving any liberty. It’s like an ideology that tells us how the program should be run or how perpetrators should be treated. In a sense if you use a paradigm, if you use an ideology to explain what is happening and then require people to apply that model solely, you actually silence - what it says at the bottom: “it silences or plays lip service to other opportunities of engaging.” In effect it patronises male victimisation concerns. It also promotes an “us and them” situation. It does not invite to dialogue at all. It labels men as perpetrators. It labels females as victims.

It says like, “because you’re a man - because you’re born a man - you are controlling and because you’re controlling you can not be a victim.” Conversely, “because you are a man, the female must be the victim, hence the female cannot be a perpetrator.” Also because of the patriarchal statement about male conditioning, males use violence to enforce authority. Females use violence in self-defence. And the same paradigm can thus not consider any other victimisation context - there may be psychopathology, mental health definitions, sorry, explanations that are not even considered. And in the last few years if you followed any research, the number of female offenders has increased dramatically, and not just in the families but also in society as a whole.

I think that the Duluth Model as we have it describes extremely well actually what the abusive behaviours are, but it does it in a very unbalanced way. Now I have one little example that I’ve used in supervision. It’s called The Constructive Feedback Model. If you take a minute to familiarise yourself with it, it states that what we do consistently well, our core quality, that if we do that too much, if we overdo it we cross a boundary, and we fall. And in the process we actually disrespect or hurt other people.

If my core quality is this then I’ve got something that I dislike in myself also. An allergy. That’s what I can’t stand in myself or in other people. I’ll give an example in a moment. What we need when we do things too much is a challenge. We need feedback, preferably constructive feedback, to bring us back into balance. But if we challenge too much, we restrict. We create extra boundaries.

I’ll give you one example. If for example my core strength, or core quality, is determination - if I’m a determined man - if I overdo it, become too determined, I will disrespect you and become a bully. I disregard other people’s opinions. What I need by way of feedback it to learn respect. What is it if I am determined, that I can’t stand: that is being uncommitted or seeing people who are uncommitted. So you can do this for yourself, a really nice exercise actually, to find out what your strengths are and where you can go wrong in overdoing them.

If I apply this to a pure feminist perspective on domestic violence, I would say, and you can challenge me on that, the core quality of that model is to point out, to describe, in a sense to reveal what has been happening. And I think they’ve done it very well over the past 40 years. However, if you overdo the describing, you cross a boundary and you start to lay down the law, you become prescribing and controlling. If my core quality is describing, what I can’t stand is covering-up - it’s actually the opposite - the minimising and the denying. What I need as a person, as a movement, as an organisation, is some challenge, some feedback that brings back some humbleness and that allows a release of restraint.

And here it is in diagram. And my last statement is “so where to from here?” and my call is for a balance. Thank you.