The World Cup Abuse Nightmare (UK/USA)

Myths about domestic violence not only libel the vast majority of men; they also put truly at-risk women at greater risk.

Do brutal attacks on women by their husbands or boyfriends surge during the World Cup? According to a May 25 press release by England’s Association of Chief Police Officers (ACPO), “cases of domestic abuse increase by nearly 30% on England match days.” The shocking 30 percent figure was from a study prepared and publicized by the British Home Office. Determined to stem the assaults, officials flooded pubs and the airwaves with graphic warnings. “Don’t let the World Cup leave its mark on you,” warned a poster distributed by the West Yorkshire Police. It showed the bare back of a cowering woman marked by bruises, cuts, and the imprint of a man’s shoe. News stories with titles such as “Women’s World Cup Abuse Nightmare” informed women that the games could uncover, “for the first time, a darker side to their partner.”

Many Americans will recall a similar scare surrounding Super Bowl Sunday in January 1993. Newspapers and television networks reported that the incidence of domestic violence increased by 40 percent during the annual football classic. Journalists were soon talking of a “day of dread” and referring to the game as the “abuse bowl.” Experts held forth on how male viewers, intoxicated and pumped up with testosterone, could “explode like mad linemen, leaving girlfriends, wives, and children beaten.” During its telecast, NBC ran a public-service announcement urging men to remain calm during the game and reminding them they could go to jail if they attacked their wives.

In that roiling sea of media credulity, Ken Ringle, a reporter at the Washington Post, did something no other reporter thought to do: He checked the facts. He quickly discovered that there was no evidence linking football and domestic violence. The source for the 40 percent factoid was a mistaken remark by an activist at a press conference in Pasadena, Calif. Today, what has come to be known as the Super Bull Sunday hoax, is a staple in discussions of urban legends. Could the World Cup Abuse Nightmare be a copycat fraud?

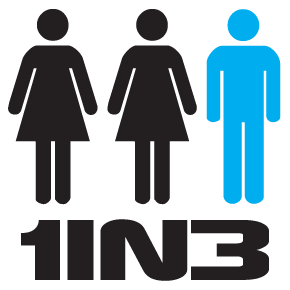

“A stunt based on misleading figures,” is the verdict of BBC legal commentator Joshua Rozenberg and producer Wesley Stephenson. They recently investigated the alleged link between the televised World Cup games and violence in the home for their weekly program Law in Action. On June 22 — day twelve of the 2010 World Cup — they aired the story. It included an interview with a prominent Cambridge University statistician, Sheila Bird, whom they had asked to review the Home Office study and its finding of a 30 percent increase in domestic abuse. She found it to be so amateurish and riddled with flaws that it could not be taken seriously. The 30 percent claim was based on a cherry-picked sample of police districts; it failed to correct for seasonal differences and essentially ignored match days that showed little or no increase in domestic violence. Professor Bird also noted that improved police practices can lead to increased reports of violence but do not necessarily indicate more violence. A telltale sign that something is amiss in the Home Office is that it also disseminates the claim that “one in four women will be a victim of domestic violence.” That impossibly high figure may be the result of a rather expansive definition of “domestic violence” — which includes not only physical and sexual violence but also emotional and “financial” abuse.