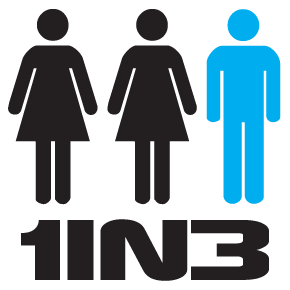

Examples of misinformation encountered since 1IN3 was founded in 2009

This page contains examples of misinformation about family violence encountered and corrected by 1IN3 since we started in 2009 along with reports of whether or not they were fixed.

Agency or Individual |

Misleading ‘statistic’ |

Correction |

Corrected? |

The Conversation Fact Check |

"FactCheck: is domestic violence the leading preventable cause of death and illness for women aged 18 to 44?" | This article contains errors. You can find a response here. | The Conversation corrected one error when notified, however one error remains. |

The Sydney Morning Herald Daily Life |

"Fact or fiction: Every third victim of intimate partner violence is a male" | This article contains a range of false and misleading information. You can find a rebuttal here. | The article remains uncorrected. |

The Tertangala |

"The One In Three Campaign is Bollocks, and Here is Why" | This article contains a range of false and misleading information. You can find a rebuttal here. | Tertangala was gracious enough to publish our rebuttal however the original article stands uncorrected. |

The Sydney Morning Herald Daily Life |

"The 'One in Three' claim about male domestic violence victims is a myth" | This article contains a range of false and misleading information. You can find a rebuttal here. | Daily Life made a small correction to their original article after a complaint to the Australian Press Council, but most of it stands uncorrected. |

The Sydney Morning Herald Daily Life |

"One-in-three myth unanimously busted on 'Hitting Home' finale of Q&A" | This article contains a range of false and misleading information. You can find a rebuttal here. | The article remains uncorrected. |

ABC Radio National AM |

“a recent survey in Victoria found family violence is the leading cause of death and ill health in women of child bearing age... It’s [family violence] the leading contributor to death and disability for women of childbearing age.” | The latest available data6 (2011) shows the top five causes of death, disability and illness combined (i.e. Disability-Adjusted Life Year, or DALY) for Australian women aged 15-44 years are anxiety disorders, depressive disorders, back pain and problems, asthma and other musculoskeletal conditions. Homicide and violence (of which family violence is a subset) ranks 26th on the list of causes. At the time the ABC broadcast their misleading 'statistic' (7/1/13), the latest available data (2003)47 showed that the top five causes of death, disability and illness [combined] for Australian women aged 15-44 years were anxiety and depression, migraine, type 2 diabetes, asthma and schizophrenia. Violence (let alone the subset of family violence) didn't make the list. | ABC's Audience and Consumer Affairs advised, “we are satisfied that the program was accurate.” |

VicHealth CEO Jerril Rechter |

“Violence against women is... the number one contributor to death and disability in Victorian women aged 15 to 44” | Intimate partner violence (not violence against women) is the leading contributor to death, disability and illness in Victorian women aged 15 to 44, according to a single, largely discredited study.32 The omission of the word illness here is critical. Deaths from intimate partner violence (femicide and suicide) made up 2.3% and 12.9% of the disease burden respectively; physical injuries just 0.7%; substance abuse (tobacco, alcohol and drug use) 10.2%; sexually transmitted infections and cervical cancer 2.2%; and poor mental health (depression, anxiety and eating disorders) 71.8%34. i.e. The vast majority of the contribution to the burden of disease in young Victorian women from intimate partner violence is from illness, not death or injury. |

VicHealth advised, “As the media release relates to a past event, no correction will be made to the document on the website. However we will ensure more consistent wording is used in the future” (in other words they are happy for their website to continue to mislead the public). |

Dr Michael Flood, University of Wollongong |

“Women are far more likely than men to experience a range of controlling tactics and experience violence after separation. Women’s perpetration of violence is much more often than men’s in self-defence. Men are more likely to perpetrate… for instrumental reasons” and many other unreferenced myths unsupported by data. |

The Australian Institute of Family Studies (1999)15 observed that, post-separation, fairly similar proportions of men (55 per cent) and women (62 per cent) reported experiencing physical violence including threats by their former spouse. Self-defence is cited by women as the reason for their use of IPV (including severe violence such as homicide) in a small minority of cases (from 5 to 20 per cent)45. After analysing for verbal aggression, fear, violence and control by each gender, husbands are found to be no more controlling than wives44. | Men's Health Australia contacted Dr Flood to ask for references to back his claims but he was unable to provide any. These 'statistics' remain uncorrected. |

Tanya Plibersek, Federal Minister for Human Services and Social Inclusion |

“Domestic violence claims more Australian women under 45 than any other health risk, including cancer” |

The top five causes of death for Australian women 15-44 years (2016) were intentional self-harm (368 deaths), accidental poisoning by and exposure to noxious substances (195 deaths), malignant neoplasm of breast (148 deaths), car occupant injured in transport accident (119 deaths) and malignant neoplasms of digestive organs (110 deaths)9. In contrast, there are 50 intimate partner homicides of women (2012-14)10. At the time Ms Plibersek made this claim (10/4/11), the top five causes of death for Australian women 15-44 years (2003) were malignant neoplasms (757 deaths), accidents and adverse affects (410 deaths), suicide and self-inflicted injury (256 deaths), diseases of the circulatory system (248 deaths) and diseases of the digestive system (81 deaths)48. In contrast, there were 54 domestic violence homicides of women49. | This ‘statistic’ remains uncorrected. |

| Kate Ellis, Federal Minister for the Status of Women | “men are more likely than women to be victims of assault (54 per cent of assault victims are men; 46 per cent are women)” | This is almost correct. The latest ABS Crime Victimisation Survey (2009-10)37 found that 56.6 per cent of assault victims were male, while 43.4 per cent were female. | This ‘statistic’ remains uncorrected. |

| “ABS statistics also show that women are more likely than men to be assaulted in their homes (41.6 per cent, compared to 21.7 per cent of men), rather than in a place of entertainment or the street.” |

This is misleading, as it appears to suggest that women are twice as likely as men to experience assault in their home. The ABS doesn't provide prevalence rates of assault by location. All they provide is an indicator of location, provided by the characteristics of the most recent incident of assault only. The latest ABS Crime Victimisation Survey (2009-10)37 found that, in the most recent incident of physical assault:

|

This ‘statistic’ remains uncorrected. | |

| "Almost 73.1 per cent of women knew their offender (compared to 21.7 per cent of men)." | This is misleading, as it appears to suggest that women are more than three times as likely as men to experience violence by known offenders. The ABS Personal Safety Survey (2006)5 provides the best data for this as it looked at overall prevalence rates, not just the most recent incident of assault. It found that while the prevalence rates for men were slightly higher than for women experiencing physical assault by known perpetrators in the last 12 months, there was no statistically significant difference between the rates. | This ‘statistic’ remains uncorrected. | |

| "Women are almost five times more likely than men to be assaulted by a partner or ex-partner." | This is incorrect. The ABS Personal Safety Survey (2006)5 provides the best data, as it looked at overall prevalence rates, not just the most recent incident of assault. It is also important to look at all victims of intimate partner violence, not just those who cohabit. It found that 28 per cent (almost one in three) victims of physical assault by an intimate partner (current partner, previous partner, boyfriend, girlfriend or date) in the last 12 months were male. | This ‘statistic’ remains uncorrected. | |

| “In relation to the suggestion that separated mothers make false accusations of violence to bolster their case in the Family Court, there is no credible research that supports the assertion that women are routinely falsifying claims of abuse to gain a tactical advantage.” |

This is incorrect. The view that some family violence order applications are unjustified appears to be shared by state magistrates in New South Wales and Queensland. Hickey and Cumines in a survey of 68 NSW magistrates concerning apprehended violence orders (AVOs) found that 90% agreed that some AVOs were sought as a tactic to aid their case in order to deprive a former partner of contact with the children. About a third of those who thought AVOs were used tactically indicated that it did not occur 'often', but one in six believed it occurred 'all the time'.39 A similar survey of 38 Queensland magistrates found that 74% agreed with the proposition that protection orders are used in Family Court proceedings as a tactic to aid a parent's case and to deprive their partner of contact with their children.40 In recently published research on the views of 40 family lawyers in NSW, almost all solicitors thought that tactical applications for AVOs occurred, with the majority considering it happened often.41 In another study based upon interviews with 181 parents who have been involved in family law disputes, there was a strong perception from respondents to family violence orders (both women and men) that their former partners sought a family violence order in order to help win their family law case.42 |

This claim remains uncorrected. | |

| “In fact research from the Australian Institute of Family Studies indicates that the opposite is the case - people are under-reporting family violence. While proceedings in the Family Court can be stressful for everyone involved, research by the Australian Institute of Family Studies indicates that the violence allegation rates during proceedings in the Family Court are similar to the reported rate in the general divorcing population. In fact, Australian research tells us that the concerns about child and family safety are very real, especially during divorce.” | It is absolutely true that people are under-reporting family violence. and that concerns about child and family safety are very real, especially during divorce. However it is also true that people are routinely falsifying claims of abuse to gain a tactical advantage in family law cases. The two aren't mutually exclusive. The government should be drafting laws to protect families and children from domestic violence, especially around the time of divorce, while at the same time protecting people from false allegations of violence and abuse which can be just as damaging. The Family Violence Bill 2011 does not do this. | This claim remains uncorrected. | |

| “Women and children are at their most vulnerable to family violence when parents are separating.” | This is misleading. Men, women and children are at their most vulnerable to family violence when parents are separating. The Australian Institute of Family Studies' evaluation of the 2006 family law reforms43 found that 39% of victims of physical hurt before separation were male; and 48% of victims of emotional abuse before or during separation were male. | This claim remains uncorrected. | |

Family Law Council |

“About one in three Australian women experience physical violence and almost one in five women experience sexual violence over their lifetime.” | About one in three Australian women and one in two Australian men experience physical violence and almost one in five women and one in eighteen men experience sexual violence over their lifetime5. | When brought to the attention of the Council, they replied “Council… does not agree that the family violence report is affected by serious statistical error.” As such, this ‘statistic’ remains uncorrected. |

|

|

“In 2005 31% of the women who reported they were physically assaulted in a 12 month period were assaulted by a current or previous partner, compared to 4.4% of men who were assaulted by a current or previous partner” | In 2005, 80.4% of persons who reported they were physically assaulted in a 12 month period by a current or previous partner were female, and 19.6% were male5. | When brought to the attention of the Council, they replied “Council… does not agree that the family violence report is affected by serious statistical error.” As such, this ‘statistic’ remains uncorrected. |

|

|

“23% of young people between the ages of 12 and 20 years had witnessed an incident of physical violence against their mother/stepmother.” | 23% of young people between the ages of 12 and 20 years had witnessed an incident of physical violence against their mother/stepmother and 22% against their father/stepfather7. | When brought to the attention of the Council, they replied “Council… does not agree that the family violence report is affected by serious statistical error.” As such, this ‘statistic’ remains uncorrected. |

Adelaide Advertiser |

“Australian women waking up this morning had a one-in-three chance the man next to them would one day ‘slap and kick’ them and then say ‘I love you, babe’” |

Just less than one in six (16.8% of) Australian women have experienced violence by a current or previous partner since the age of 155. | This ‘statistic’ remains uncorrected. |

Adelaide Advertiser |

“a quarter of Australian children had witnessed violence against their mother” |

This statistic is taken from the source study Young people and domestic violence - national research on young peoples attitudes to and experiences of domestic violence7. This study found that while 23% of young people were aware of domestic violence against their mothers or step-mothers by their fathers or step-fathers, an almost identical proportion (22%) of young people were aware of domestic violence against their fathers or step-fathers by their mothers or step-mothers. Even more importantly, while similar proportions of young people were aware of exclusive violence by their mother/stepmother or father/step-father, a much greater proportion of young people experienced couple violence between their parents/step-parents. The study was quite unequivocal when reporting on the effects of young people witnessing domestic violence, finding that the most severe disruption on all available indicators occurred in households where couple violence was reported. | This ‘statistic’ remains uncorrected. |

Adelaide Advertiser |

“the poor attitude of Australian men to violence against women was evidenced by a 2006 Victorian survey which found one in 20 believed women who were raped often ‘ask for it’” |

The survey found that 6% (around 1 in 20) people (not men) agreed with the statement ‘Women who are raped often ask for it’33. | This ‘statistic’ remains uncorrected. |

Courier Mail |

“Violence hits females most” (QLD, 2008-09) |

Total Offences Against the Person for Queensland were 15,294 for males and 13,573 for females36. | This ‘statistic’ remains uncorrected. |

|

|

“Across all age groups females are much more likely to be victims than males” (QLD, 2008-09) |

Females are more likely to be victims than males in the age groups 0-17, but for all age groups 18 and over, males are more likely to be victims than females36. | This ‘statistic’ remains uncorrected. |

Amnesty International |

“In some countries up to 69% of women have been physically abused by their male partners” |

The 69% statistic was calculated from a regional survey of 378 ever-married/partnered women aged 15 to 49 in Nicaragua1. This data was not nationally representative, it only surveyed young women, and it excluded women who had never been married/partnered. A nationally representative study with a much larger sample size2 found an overall lifetime prevalence of physical violence from a partner of 28%. | Commendably, Amnesty have stopped using this ‘statistic’. |

|

|

“Violence against women is the most widespread human rights abuse in the world” |

Violence against men, on every available indicator, is much more extensive, widespread, and has much greater health impacts, than does violence against women3. | Commendably, Amnesty have reworded the ‘statistic’ to read “Violence against women is one of the most widespread human rights abuses in the world.” |

|

|

“The Council of Europe has stated that domestic violence is the major cause of death and disability for women aged 16 to 44 and accounts for more death and ill-health than cancer or traffic accidents” |

Cancer is responsible for 3.4 times the burden of disease, and road traffic accidents 2.3 times the burden, compared to (all) violence (not just domestic violence)4. | Commendably, Amnesty have stopped using this ‘statistic’. |

Oxfam |

“For women aged 15-44 gender violence accounts for more deaths and disability than cancer, malaria, traffic accidents and war” |

Cancer is responsible for 3.4 times the burden of disease, and road traffic accidents 2.3 times the burden, compared to (all) violence (not just gender violence)4. | This ‘statistic’ remains uncorrected. |

Australian Broadcasting Corporation |

“More than one in three Australian women will experience violence inflicted by their partner at some point in their lifetime” |

The most recent nationally representative survey found that 1 in 48 Australian women report having experienced violence from a current partner since the age of 155. | Commendably, the ABC have amended the ‘statistic’ on their website. |

|

|

“Violence is the leading cause of death, disability and illness to Victorian women under the age of 45” |

The latest available data6 (2011) shows the top five causes of death, disability and illness combined (i.e. Disability-Adjusted Life Year, or DALY) for Australian women aged 15-44 years are anxiety disorders, depressive disorders, back pain and problems, asthma and other musculoskeletal conditions. Homicide and violence ranks 26th on the list of causes. At the time the Australian Broadcasting Corporation broadcast their misleading 'statistic' (25/11/2008),47 ;the top five causes of death, disability and illness [combined] for Australian women 15-44 years were anxiety and depression, migraine, type 2 diabetes, asthma and schizophrenia . Violence didn't make the top ten leading causes. | Commendably, the ABC have added a footnote to clarify this ‘statistic’ on their website. |

|

|

“Every year, nearly half a million Australian women experience violence at the hands of their partners or ex-partners” |

The most recent nationally representative survey found that 114,600 Australian women report having experienced violence from a current or previous partner during the last 12 months5. | Commendably, the ABC have removed this ‘statistic’ from their website. |

White Ribbon Foundation |

“In contrast to men’s experience of violence, male violence against women generally takes place within family and other relationships” |

Australian men and women were equally likely to be physically assaulted by persons known to them during the last 12 months5. | This ‘statistic’ remains uncorrected. |

|

|

“There has yet to be any work done on the impact of violence on men’s overall health, i.e. its contribution to the burden of disease. We, therefore, don’t yet know the impact of men’s violence against men from a public health point of view.” |

The contribution of violence to the burden of disease in both men and women has been studied for many years. The most recent data from the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare found that homicide and violence contributed 18,527 disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) in male victims, and 7,530 DALYs in female victims6. At the time White Ribbon made the claim on their website, the most recent data from the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare found that homicide and violence contributed 6,535 disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) in male victims, and 2,686 DALYs in female victims47. | This ‘statistic’ remains uncorrected. |

|

|

“[violence against women] is internationally recognised as a significant social problem worldwide and in Australia – with one in three women experiencing violence in her lifetime.” |

Violence is internationally recognised as a significant social problem worldwide and in Australia – with two in five women, and one in two men experiencing violence in their lifetime5. | This ‘statistic’ remains uncorrected. |

|

|

“Canadian research tells us that women are three times more likely to be injured, five more times likely to be hospitalised and five times more likely to report fearing for their lives as a result of [intimate partner] violence” |

These statistics are from an out-of-date Canadian survey (Statistics Canada 2003). The latest survey, “Family Violence in Canada: A Statistical Profile” (Statistics Canada 2008), found that similar percentages of female and male victims sustained injuries, and that male victims of spousal violence are 1.8 times as likely as female victims of spousal violence to suffer major assault16. | This ‘statistic’ remains uncorrected. |

|

|

“What makes Violence against Women different?… Violence against women is most often sustained, based on maintaining power and control and contextualised by psychological and emotional abuse.” |

The recent Australian Intimate Partner Abuse of Men study found that all these characteristics applied equally to male victims35. | This ‘statistic’ remains uncorrected. |

|

|

“Intimate Partner Violence is the leading contributor to death and disability among women aged 15 to 44.” |

Intimate partner violence is the leading contributor to death, disability and illness in Victorian women aged 15–44. The omission of the word illness here is critical. Deaths from intimate partner violence (femicide and suicide) made up 2.3% and 12.9% of the disease burden respectively; physical injuries just 0.7%; substance abuse (tobacco, alcohol and drug use) 10.2%; sexually transmitted infections and cervical cancer 2.2%; and poor mental health (depression, anxiety and eating disorders) 71.8%. i.e. The vast majority of the contribution to the burden of disease in young Victorian women from intimate partner violence is from illness34. | This ‘statistic’ remains uncorrected. |

|

|

“There is no evidence that male victims are more likely to under-report [domestic violence] than female victims” | The large-scale South Australian Interpersonal Violence and Abuse Survey found that “females (22.0%) were more likely to report the [domestic violence] incident(s) to the police than males (7.5%)”22. | This ‘statistic’ remains uncorrected. |

|

|

“Males are more likely than females to agree with statements [such as]... ‘when a guy hits a girl it's not really a big deal’” |

31% of young males and 19% of young females agreed with the statement “when girl hits a guy its really not a big deal.” The same survey found that while males hitting females was seen, by virtually all young people surveyed, to be unacceptable, it appeared to be quite acceptable for a girl to hit a boy7. | This error was widely reported as fact by the Australian media, politicians and NGOs. Commendably, the WRF issued a correction, and subsequently some media outlets such as the ABC corrected their reports, while most others remain uncorrected. |

|

|

“In a survey of 5,000 young Australians aged 12-20: One in four (23.4%) reported having witnessed an act of physical violence by their father or step-father against their mother or step-mother (this included throwing things at her, hitting her, or using a knife or a gun against her, as well as threats and attempts to do these things). Over half (58%) had witnessed their father or stepfather yell loudly at their mother/step mother” |

In the same survey, 22% of young Australians reported having witnessed an act of physical violence by their mother or step-mother against their father or step-father (this included throwing things at him, hitting him, or using a knife or a gun against him, as well as threats and attempts to do these things). Over half (55%) had witnessed their mother or stepmother yell loudly at their father/step father7. | This misleading selective use of data was widely reported by the Australian media, politicians and NGOs. It remains uncorrected. |

|

|

“30.2% of Year 10 girls and 26.6% of Year 12 girls have ever experienced unwanted sex” |

22.6% of Year 10 boys and 23.8% of Year 12 boys had also experienced unwanted sex8. | This misleading selective use of data was widely reported by the Australian media, politicians and NGOs. It remains uncorrected. |

|

|

“The National Crime Prevention survey found that... 6% [of young women] said a boyfriend had physically forced them to have sex” |

The same survey found that 5% of young men said a girlfriend had physically forced them to have sex7. | This misleading selective use of data was widely reported by the Australian media, politicians and NGOs. It remains uncorrected. |

|

|

“For young women the risk of violence is 3 to 4 times higher than the risk for women overall” |

For young women the risk of violence is 2.1 times higher than the risk for women overall5. | Commendably, the WRF corrected this error. |

|

|

“The 2006 Australian Bureau of Statistics survey found that 27.2% of women aged 18-24 had experienced an incident of physical assault in the past 12 months compared to 12% of older women” |

The 2006 Australian Bureau of Statistics survey found that 7% of women aged 18-24 had experienced an incident of physical assault in the past 12 months compared to 2% of older women5. | Commendably, the WRF corrected this error. |

Australian Democrats |

“According to the ABS almost 6% of all women were hurt by family violence during 2005.” |

According to the ABS 5.8% of all women were hurt by violence (of all forms) during 2005. Approximately 1.5% of all women were hurt by family violence (by a current or previous partner) during 20055. | This ‘statistic’ remains uncorrected. |

|

|

“A third of them [all women] were sexually assaulted by a partner.” | Of the 1.3% of all women who reported being sexually assaulted, 7.7% of them were assaulted by a current partner, and 21.1% of them were assaulted by a previous partner in the most recent incident. This means approximately 0.4% of all women were sexually assaulted by a partner5. | This ‘statistic’ remains uncorrected. |

|

|

“Women are most at risk while they are pregnant.” | 14.6% of women who had experienced violence by a current partner and 35.9% of women who had experienced violence by a previous partner since the age of 15 reported that violence occurred during a pregnancy5. | This ‘statistic’ remains uncorrected. |

The Hon. Linda Burney MP, NSW Minister for Women |

“domestic violence affects one in three women in Australia” |

The most comprehensive, recent and largest scale survey on violence in Australia found that approximately one in six Australian women will be affected by domestic violence (violence from a current or former partner) over their lifetimes. On an annual basis, domestic violence affects approximately one in sixty-seven women5. | This ‘statistic’ remains uncorrected. |

|

|

“[domestic violence] is the most likely form of preventable deaths for women under the age of 45” |

The top five causes of death for Australian women 15-44 years (2016) were intentional self-harm (368 deaths), accidental poisoning by and exposure to noxious substances (195 deaths), malignant neoplasm of breast (148 deaths), car occupant injured in transport accident (119 deaths) and malignant neoplasms of digestive organs (110 deaths)9. In contrast, there are 50 intimate partner homicides of women (2012-14)10. At the time Ms Burney made this claim, the top five causes of death for Australian women 15-44 years were malignant neoplasms (757 deaths per annum), accidents and adverse affects (410 deaths), suicide and self-inflicted injury (256 deaths), diseases of the circulatory system (248 deaths) and diseases of the digestive system (81 deaths)48. There were 54 domestic violence homicides of women annually49. | This ‘statistic’ remains uncorrected. |

|

|

“women and children fleeing domestic violence form the largest group of homeless people in our country” |

While domestic/family violence is the main reason cited for seeking assistance from Supported Accommodation Assistance Program (SAAP) agencies11, the need for housing/accommodation is just one of many reasons why people approach SAAP agencies (other non-accommodation services provided include financial/employment, personal support, advocacy and specialist services). SAAP agencies accommodate just 15% of the Australians who experience homelessness on any given night12, the majority (58%) of whom are men13. | This ‘statistic’ remains uncorrected. |

NSW Government, Department of Premier and Cabinet, Office for Womens Policy |

“As numerous studies show, the majority of violence that women experience is perpetrated by an intimate male partner. The most recent Australian Bureau of Statistics Personal Safety Survey found that most women assaulted in the last 12 months were assaulted by either a current or previous partner” |

The most recent Personal Safety Survey found that 30% of women assaulted in the last 12 months were assaulted by either a current or previous partner5. | Commendably, the NSW Government have issued errata correcting this ‘statistic’. |

|

|

“Only a very small proportion of assaults against men were perpetrated by a former or current female intimate partner (4.3%)” |

The most recent Personal Safety Survey found that males make up 20% of victims of violence by former or current partners5. | This ‘statistic’ remains uncorrected. |

|

|

“Three quarters of intimate partner homicides involve men killing their female partners” |

The latest Homicide in Australia: 2006-07 National Homicide Monitoring Program annual report found that less than two thirds (64.6%) of intimate partner homicides involve men killing their female partners14. | This ‘statistic’ remains uncorrected. |

|

|

“Data from the Personal Safety Survey also indicates that women reporting violence in intimate relationships are significantly more likely than men to experience repeated acts of violence” |

Data from the Personal Safety Survey indicates that women reporting violence by current partners in intimate relationships are significantly more likely than men to experience repeated acts of violence. However, women and men reporting violence by previous partners in intimate relationships experience repeated acts of violence at similar rates5. | Commendably, the NSW Government have issued errata correcting this ‘statistic’. |

|

|

“Males did not have prior experiences of violent relationships” |

The Personal Safety Survey shows that 6% of males and 17% of females have prior experiences of violent relationships (i.e. they have experienced current or previous partner violence since the age of 15)5. | This ‘statistic’ remains uncorrected. |

|

|

“Males rarely experienced post separation violence” |

The Personal Safety Survey shows that 5% of males (n = 367,300) and 15% of females (n = 1,135,500) have experienced previous partner violence since the age of 155. Research by the Australian Institute of Family Studies made the following observations about post separation violence. (a) Fairly similar proportions of men (55%) and women (62%) reported experiencing physical violence including threats by their former spouse. (b) Emotional abuse was reported by 84% of women and 75% of men15. | This ‘statistic’ remains uncorrected. |

|

|

“Canadian data indicate that compared with male victims of domestic violence, women are three times more likely to be injured as a result of violence; five times more likely to require medical attention or hospitalisation” |

These statistics are from an out-of-date Canadian survey. The latest survey found that similar percentages of female and male victims sustained injuries and male victims of spousal violence are 1.8 times as likely as female victims of spousal violence to suffer major assault16. | This ‘statistic’ remains uncorrected. |

|

|

“In addition, a study in the United States comparing the mental health impacts of domestic violence for men and women found that women were markedly more likely to suffer impacts than men” |

While the referenced study of 502 university students17 did find that the mental health impacts of domestic violence on women were markedly greater than on men, it also found that for experienced and witnessed family violence, the health impact was similar for males and females. A further study of 573 university students found that reporting higher number of mental health symptoms was significantly related to experiencing higher levels of IPV victimisation but not to gender (female or male)18. | This ‘statistic’ remains uncorrected. |

|

|

“Compared to men, women comprise the majority of domestic and family violence victims brought to the attention of criminal justice agencies. An analysis of reported incidents of domestic assault in NSW between 1997 and 2004 indicated that 71% of domestic assault incidents reported to the police involved a female victim, and that 80% of the offenders were male. By these figures, 29% of victims were male, not an insignificant proportion. A possible explanation for this is given by Flood. On his analysis, the data relied upon may be categorised as being drawn from acts based instruments. Flood argues that such instruments have value as surveillance instruments in the general population but they are inadequate for capturing the substance, impact or dynamics of intimate partner violence, and particularly the more serious forms of this violence, which women experience at far greater rates than men. In this regard, whilst the figures show a not insignificant proportion of men experiencing domestic violence, they do not capture the seriousness of that violence” |

The NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research data19 showing that 29% of domestic assault victims are male is crime data (based upon reports to police) and therefore does not rely whatsoever upon the acts based instruments used to obtain survey data. However, the statistics quoted on page 3 of the discussion paper from the Personal Safety Survey5 and the International Violence Against Women Survey20 rely exclusively upon acts based instruments. Dr Flood's critique can therefore be applied only to data from these surveys, and is not a valid or relevant critique of the NSW crime data. | This error remains uncorrected. |

|

|

“Exposure to domestic and family violence increases... and, in the case of boys particularly, may lead to them perpetrating violence as adults” |

The referenced paper Young Australians and Domestic Violence21 says nothing whatsoever about boys being more likely than girls to perpetrate violence as adults if exposed to domestic and family violence as children. It instead talks generically of young people. | Commendably, the NSW Government have issued errata correcting this ‘statistic’. |

|

|

“Domestic and family violence can be lethal. In Australia from 1989 to 1998, 57% of female deaths resulting from homicide or violence were perpetrated by an intimate partner, with women being over five times more likely to be killed by an intimate partner than men” |

The latest Homicide in Australia: 2006-07 National Homicide Monitoring Program annual report14 found that 52% of female homicides were perpetrated by an intimate partner and women were 1.8 times as likely to be killed by an intimate partner than men. | This error remains uncorrected. |

|

|

“According to national data, women who experience domestic and family violence do not report it to police. Approximately 14% of women who experienced violence from an intimate partner reported the most recent incident to police” |

While it is indisputable that many women who experience domestic and family violence do not report it to police, the Discussion Paper fails to acknowledge that men who experience such violence are even less likely than women to report it to the authorities. The comprehensive South Australian Interpersonal Violence and Abuse Survey22 found that 22% of female victims but only 7.5% of male victims reported their domestic violence incidents to the police. | This misleading selective use of data remains uncorrected. |

|

|

“One in four 12-20 year old Australians surveyed was aware of domestic violence against their mothers or stepmothers by their fathers or step-fathers” |

This statistic is taken from the source study Young people and domestic violence - national research on young peoples attitudes to and experiences of domestic violence7. This study found that while 23% of young people were aware of domestic violence against their mothers or step-mothers by their fathers or step-fathers, an almost identical proportion (22%) of young people were aware of domestic violence against their fathers or step-fathers by their mothers or step-mothers. Even more importantly, while similar proportions of young people were aware of exclusive violence by their mother/stepmother or father/step-father, a much greater proportion of young people experienced couple violence between their parents/step-parents. The study was quite unequivocal when reporting on the effects of young people witnessing domestic violence, finding that the most severe disruption on all available indicators occurred in households where couple violence was reported. | This misleading selective use of data remains uncorrected. |

|

|

“Family and domestic violence is a common cause of marital breakdown - 60% of couples cite family violence as a contributing factor in the breakdown of marriages and 30% describe it as a major reason why their relationship ended” |

The Discussion Paper cites as the source for this statistic, Impact of the Family Law Amendment (Shared Parental Responsibility) Act 2006 (Cth)23. This document in turn cites a submission to the Inquiry by the National Abuse Free Contact Campaign24. This submission refers to source research by the Australian Institute of Family Studies (AIFS). When one looks at the source AIFS research15, it actually found that 6% of respondents reported that physical violence was the main reason for marriage breakdown; and verbal and emotional abuse was cited as a main reason by only 2% of respondents. | This ‘statistic’ remains uncorrected. |

Government of South Australia, Office for Women |

“Domestic violence costs the Australian economy approximately 13.6 billion every year. This figure is expected to rise to 15.6 billion by 2021-22. At a total cost of 3.5 billion, it has been established that pain, suffering and premature mortality accounts for nearly half the total cost of domestic violence. The next largest contributor is consumption costs, including property replacement, bad debts and lost household economics” |

These costs25 do not apply just to domestic violence. They apply to all violence against women and their children and include both domestic (intimate and ex-intimate partner) and non-domestic violence. They do not include the cost of domestic violence against men (who make up over one third26 of victims). |

Commendably, the OfW have reworded this ‘statistic’ to read “Violence against women and their children was estimated to cost...” |

|

|

“Three women are killed in domestic violence situations every fortnight across Australia” |

Two women and one man are killed in domestic violence situations every two-and-a-half weeks across Australia. 42 females and 23 males were victims of intimate partner homicide in 2006-07 (the most recent data available)14. | Commendably, the OfW have stopped using this ‘statistic’ |

|

|

“It is estimated that in every year, approximately 350,000 and 125,000 will experience physical and sexual violence respectively” |

It is estimated that in every year in Australia, approximately 350,000 and 125,000 women will experience physical and sexual violence respectively. So will approximately 775,000 and 45,000 men. These figures refer to all violence, not just domestic violence, and they include attempts and threats as well as actual violence. As far as domestic violence goes, it is estimated that in every year in Australia, approximately 114,600 women will experience domestic violence (43,800 from their current partner, and 70,800 from their former partner). So will 27,900 men (8,400 from their current partner, 19,500 from their former partner). In total 142,500 people will experience domestic violence every year5. | Commendably, the OfW have stopped using this ‘statistic’ |

|

|

“Domestic violence is the main cause of death, disability and illness in Victorian women 15-44 years. It is more harmful than smoking, alcohol and obesity combined” |

The top five causes of death, disability and illness [combined] for Australian women 15-44 years are anxiety and depression, migraine, type 2 diabetes, asthma and schizophrenia. Violence doesnt make the top ten leading causes6. At the time the Office for Women published their website (21/5/10),47 the top five causes of death, disability and illness [combined] for Australian women 15-44 years were anxiety and depression, migraine, type 2 diabetes, asthma and schizophrenia. Violence didn't make the top ten leading causes. | Commendably, the OfW have reworded this ‘statistic’ to read “Intimate partner violence is responsible for more ill-health and premature death in Victorian women under the age of 45 than any other of the well-known risk factors, including high blood pressure, obesity and smoking.” |

|

|

“At least 1 in 17 women is a victim of domestic violence each year” |

At least 1 in 67 women is a victim of domestic violence each year. These figures include attempts and threats as well as actual violence5. | Commendably, the OfW have stopped using this ‘statistic’ |

|

|

“1 in 8 high school students will be in a domestic violence relationship before they leave school” |

1 in 8 high school students will be in a domestic violence relationship before they leave school. Approximately equal numbers of victims will be male and female7. | Commendably, the OfW have stopped using this ‘statistic’ |

|

|

“95% of domestic violence involves a male perpetrator and a female victim. The other 5% includes same sex relationships or a female perpetrator to the victim” |

Up to two-thirds of domestic violence victims are female, and at least one third are male26. | Commendably, the OfW have stopped using this ‘statistic’ |

|

|

“About 7% of non-Aboriginal women reported experiencing physical violence during 2005, compared to 20% of aboriginal women” |

About 7% of non-Aboriginal women reported experiencing physical violence during 2002, compared to 20% of Aboriginal women20. This figure includes both domestic (intimate and ex-intimate partner) and non domestic violence against women by men, includes attempts and threats as well as actual violence, and does not include violence against women by other women (which makes up approximately one-quarter of all violence against women5). | Commendably, the OfW have stopped using this ‘statistic’ |

|

|

“Young women experience higher rates of sexual assault and run higher risks, at least 3 to 4 times higher, than the overall population of women” |

Young people experience higher rates of sexual assault and run higher risks, at least twice as high as the overall population5. | Commendably, the OfW have reworded this ‘statistic’ to read “The [Personal Safety] survey also found that young women experience sexual assault at higher rates than older women” |

|

|

“25% of young people have witnessed physical domestic violence against their mother” |

23% of young people have witnessed physical domestic violence against their mother or stepmother, and 22% of young people have witnessed physical domestic violence against their father or stepfather7. | Commendably, the OfW have stopped using this ‘statistic’ |

Sex Discrimination Commissioner, Ms Elizabeth Broderick |

“One in three women will live in an intimate relationship characterised by violence over her lifetime” |

The Personal Safety Survey 20055 found that 160,100 women have experienced violence from a current partner since the age of 15. This is 2.08% of Australian women. This equates to one in forty eight women - nowhere near one in three. | This ‘statistic’ remains uncorrected. |

|

|

“almost 90% of the victims of domestic violence are female” |

Up to two-thirds of domestic violence victims are female, and at least one third are male26. | This ‘statistic’ remains uncorrected. |

Prime Minister Kevin Rudd |

“In any year, nearly half a million Australian women experience physical or sexual assault by a current or former partner” |

The most recent nationally representative survey5 found that 114,600 Australian women report having experienced violence from a current or previous partner during the last 12 months. | This ‘statistic’ remains uncorrected. |

The National Council to Reduce Violence against Women and their Children |

“many men belong to sexist peer cultures” |

The vast majority of men believe in gender equality7. | This unfortunate statement remains uncorrected. |

|

|

“domestic and family violence is a common cause of relationship breakdown” |

Only 7% of breakdowns are caused by violence or abuse: communication problems are the main cause15. | This error remains uncorrected |

|

|

“63% of child killers are fathers” |

Less than a quarter are fathers, and over half are mothers27. | This ‘statistic’ remains uncorrected |

|

|

“Australian women and their children have a right to protection from violence” |

International human rights conventions apply equally to all people28. | This one-sided statement remains uncorrected. |

|

|

“denigrating representations of women in the media should be addressed” |

Negative portrayals of men are far more prevalent and just as damaging29. | This one-sided statement remains uncorrected. |

Professor Thea Brown, Director, Well Being of Children Following Parental Separation and Divorce Research Consortium, Monash University |

“Earlier studies suggest that domestic violence is the major cause of parental separation in 66% of parental relationship breakdowns. For 33% of these couples, the violence can be categorised as serious. Research also shows that in some demographics and some regional areas, family violence can be a contributing factor to separation in 80% of cases” |

Only 7% of breakdowns are caused by violence or abuse: communication problems are the main cause15. | These ‘statistics’ remain uncorrected. |

United Nations Population Fund |

“Violence is a traumatic experience for any man or woman, but gender-based violence is preponderantly inflicted by men on women and girls”. No evidence is cited for this claim. However, the following circular argument is offered instead. “Definition of gender-based violence: Any act of gender-based violence that results in, or is likely to result in, physical, sexual or psychological harm or suffering to women, including threats of such acts, coercion or arbitrary deprivations of liberty, whether occurring in public or in private life” |

It would only be fair if male victims weren't defined out of existence by United Nations reports such as these. | This attempt to deny the existence of male victims of violence remains uncorrected. |

United Nations Millennium Project |

“Worldwide, it is estimated that violence against women is as serious a cause of death and incapacity among reproductive-age women as is cancer, and it is a more common cause of ill-health among women than traffic accidents and malaria combined” |

Cancer is responsible for 3.4 times the burden of disease, and road traffic accidents 2.3 times the burden, compared to violence4. | This ‘statistic’ remains uncorrected |

World Health Organisation |

“Where violence by women occurs it is more likely to be in the form of self-defence” |

The references cited to back this claim all asserted that womens violence was primarily in self defense, but either reported no data, or reported that only 6.9% of the women acted in self-defense. At least five other un-cited studies report data on self-defense. Four out of the five found that only a small percentages of female violence was in self-defense. For the one study which found high rates of self-defense, the percentage in self-defense was slightly greater for men (56%) than for women (42%)30. | This ‘statistic’ remains uncorrected |

Kelvin Thomson MP, Federal Member for Wills |

“Violence is the biggest health risk to Australian women” |

The biggest health risks to Australian women are tobacco use, overweight/obesity, physical inactivity, blood pressure and alcohol use46. At the time Mr Thomson made this claim, the biggest health risks to Australian women were high blood pressure, high body mass, physical inactivity and tobacco47. | This ‘statistic’ remains uncorrected |

Mrs Sophie Mirabella MP, Shadow Minister for Women |

“1 in 3 teenage boys think its no big deal to hit a girl... almost a third of girls in year 10 have experienced unwanted sex” |

31% of young males and 19% of young females agreed with the statement “when a girl hits a guy its really not a big deal.” The same survey found that while males hitting females was seen, by virtually all young people surveyed, to be unacceptable, it appeared to be quite acceptable for a girl to hit a boy7. 22.6% of Year 10 boys have also experienced unwanted sex8. | These ‘statistics’ remain uncorrected. |

Ms Pru Goward MP, Shadow Minister for Women |

“I am... very disappointed that so many young men believe it's acceptable to hit your girlfriend... We don't know whether boys have always held these attitudes or whether they've got worse because we actually haven't been doing this sort of research, but it is a very high level of tolerance of violence and a belief that violence is okay” |

31% of young males and 19% of young females agreed with the statement “when girl hits a guy its really not a big deal.” The same survey found that while males hitting females was seen, by virtually all young people surveyed, to be unacceptable, it appeared to be quite acceptable for a girl to hit a boy7. | Commendably, the ABC have amended the ‘statistic’ on their website. |

Graeme Innes, Human Rights and Disability Discrimination Commissioner and Tom Calma, Torres Strait Islander Social Justice and Race Discrimination Commissioner |

“one in three boys think that it is OK to hit a girl” |

31% of young males and 19% of young females agreed with the statement “when girl hits a guy its really not a big deal.” The same survey found that while males hitting females was seen, by virtually all young people surveyed, to be unacceptable, it appeared to be quite acceptable for a girl to hit a boy7. | Commendably, the Australian Human Rights Commission has amended this ‘statistic’ on their website. |

|

|

“research finds that one in four 12 to 20 year olds are aware of domestic violence being committed against their mothers or step-mothers by their fathers or step fathers” |

The same research finds that 22% of young Australians reported having witnessed an act of physical violence by their mother or step-mother against their father or step-father7. | This misleading selective use of data remains uncorrected. |

Andrew O'Keefe, Chairman White Ribbon Foundation, White Ribbon Ambassador and member of the National Council for Reducing Violence Against Women and their Children |

“Violence against women is the most prevalent human rights abuse in the world” |

Violence against men, on every available indicator, is much more extensive, widespread, and has much greater health impacts, than does violence against women3. | This ‘statistic’ remains uncorrected |

|

|

“many more Australian girls suffer physical... violence than Australian boys” |

The Personal Safety Survey 20055 found that 702,400 males and 779,500 females had experienced physical abuse before the age of 15. The National Crime Prevention Survey7 found that young females were more likely than young males to have experienced bitching and rape/sexual assault, while young males were more likely than young females to have experienced bullying, punch-ups between people at school/college, drunken fights in pubs/clubs and racial violence. Young males and females were equally likely to have experienced physical fights between brothers and sisters and domestic violence. | This ‘statistic’ remains uncorrected |

|

|

“One in three boys believes most violence against women occurs because the woman provoked it” |

The study actually found that 33% of young males and 25% of young females agreed with the statement “Most physical violence occurs in dating because a partner provoked it.” These young males and females were equally likely to have experienced domestic violence7. | This ‘statistic’ remains uncorrected |

|

|

“One in three year 10 girls who've had sex, have had unwanted (i.e. coerced) sex” |

22.6% of Year 10 boys have also experienced unwanted sex. Only 13.4% of young people who had experienced unwanted sex, had been 'coerced' ('my partner thought I should' or 'my friends thought I should'). Other reasons given for unwanted sex were 'too drunk' or 'too high')8. | This misleading selective use of data remains uncorrected. |

|

|

“[Violence against women] outstrips breast cancer, obesity, drink-driving and smoking as the leading contributor to death, disability and illness for women in the prime of their life.” |

According to a VicHealth study with flawed methodology, intimate partner violence outstrips illicit drugs, alcohol, body weight, cholesterol, tobacco, blood pressure and physical inactivity as the leading contributor to death, disability and illness for Victorian women aged 15-4432. Both breast cancer and road traffic accidents contribute more to the burden of disease in women aged 15-44 than does violence6. | This misleading selective use of data remains uncorrected. |

Jon Chin, member of the Hunter White Ribbon Day breakfast organising committee |

“Violence against women has to be the greatest human rights scandal of our time” |

Violence against men, on every available indicator, is much more extensive, widespread, and has much greater health impacts, than does violence against women3. | This ‘statistic’ remains uncorrected |

|

|

“more than 1 million women had been a victim of violence in the previous 12 months” |

443,800 women had been a victim of violence in the previous 12 months, as had 808,300 men5. | This ‘statistic’ remains uncorrected |

|

|

“one in seven boys aged 12 to 20 believes it is all right to force a girl to have sex if she was flirting” |

One in eight boys aged 12 to 20 said yes to the statement ‘It’s okay for a boy to make a girl have sex, if she’s flirted with him, or led him on’7. | This ‘statistic’ remains uncorrected |

|

|

“One in three boys believes most violence against women occurs because the woman provoked it” |

The study actually found that 33% of young males and 25% of young females agreed with the statement ‘Most physical violence occurs in dating because a partner provoked it.’ These young males and females were equally likely to have experienced domestic violence. The same survey found that while males hitting females was seen, by virtually all young people surveyed, to be unacceptable, it appeared to be quite acceptable for a girl to hit a boy7. | This ‘statistic’ remains uncorrected |

Fran Bailey, Federal Member for McEwen |

“many young boys still thought it was acceptable to hit girls” |

31% of young males and 19% of young females agreed with the statement “when girl hits a guy its really not a big deal.” The same survey found that while males hitting females was seen, by virtually all young people surveyed, to be unacceptable, it appeared to be quite acceptable for a girl to hit a boy7. | This ‘statistic’ remains uncorrected |

Access Economics |

“98% of perpetrators [of domestic violence] were male” |

65% of domestic violence perpetrators were male, according to available Australian data at the time31. | Commendably, Access Economics released a corrigendum revising this figure to 87%. Unfortunately this figure is still incorrect, as it is based on out-of-date United States survey data and incorrect calculation methodology. |

The Body Shop |

“98% of the perpetrators of domestic violence were male” |

65% of domestic violence perpetrators were male, according to available Australian data at the time31. | Commendably, the Body Shop corrected this error, revising this figure to 87%. Unfortunately this figure is still incorrect, as it is based on out-of-date United States survey data and incorrect calculation methodology. |

Marie Claire Magazine |

“that's half a million children and teenagers who know their mother or step-mother is being abused by her partner” |

An almost identical number of children and teenagers know their father or step-father is being abused by his partner7. | This ‘statistic’ remains uncorrected |

US Congressman William Delahunt, co-sponsor of the International Violence Against Women Act |

“The World Health Organization estimates that violence against women causes more disability and death among women aged 15 to 44 than cancer, malaria, traffic accidents and war” |

The World Health Organisation reports that cancer is responsible for 3.4 times the burden of disease, and road traffic accidents 2.3 times the burden, compared to violence4. | This error was widely reported by Australian and International media, and remains uncorrected. |

1 Morrison, Andrew R. and Maria Beatriz Orlando (1999). “Social and economic costs of domestic violence: Chile and Nicaragua.” In Too Close to Home: Domestic Violence in the Americas. Eds. Andrew R. Morrison and M.L Biehl. Washington, DC: Inter- American Development Bank. Pp. 51-80.

2 Rosales, Jimmy, Edilberto Loaiza, Domingo Primante, Angeles Barberena, Luîs Blandon, and Mary Ellsberg (1999). Encuesta Nicaragüense de Demografia y Salud 1998. Managua, Nicaragua: Instituto Nacional de Estadîsticas y Censos, INEC.

3 N.B. These figures include all violence against men, not just family violence. They are included here because ‘violence against women’ is often erroneously conflated with ‘domestic violence’. Prevalence of violence: the Australian Bureau of Statistic (ABS) 2005 Personal Safety Survey found that 10.8% (n = 808,300) of men and 5.8% (n = 443,800) of women had experienced violence during the last 12 months (and this survey excluded forms of violence experienced predominantly by men, such as violence during the course of play on a sporting field and rape and physical assault amongst the prison population). That means Australian men are almost twice as likely as women to be victims of violence. Impacts of violence: The World Health Organisation (WHO) collects data from around the world on the burden of disease. This disease burden includes four different categories of violence: self-inflicted injuries, violence, war and civil conflict, and other intentional injuries. The impacts of these forms of violence on the lives of victims are measured in a number of ways. One way is to measure the number of deaths from violence. When one does this, one finds that male deaths outnumber female deaths in a ratio of over 2.5 to 1. Another measure of the impact of violence upon victims is called the DALY, or Disability Adjusted Life Year. The DALY is a measure of overall disease burden. It is designed to quantify the impact of premature death and disability on a population by combining them into a single, comparable measure. In so doing, mortality and morbidity are combined into a single, common metric. When one looks at the DALY measures for the categories of violence listed above, one finds that the burden of disease from violence for males is over 2.8 times greater than the burden for females. This data on deaths and DALYs shows that the impact of violence upon males is greater than upon females across all geographic regions, races, religions, classes, cultures and ages (though young men experience the greatest impacts of violence of any age group). The one exception is the overall disease burden (DALYs) from self-inflicted injuries in the Western Pacific Region, where females suffer an almost 10% greater burden than males.

4 The most recent World Health Organisation (WHO) Global Burden of Disease figures can be found on the WHO website at http://www.who.int/entity/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/DALY6%202004.xls

5 Australian Bureau of Statistics (2006). Personal safety survey australia: 2005 reissue 4906.0. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics. (Original work published August 10, 2006) Retrieved September 21, 2009, from http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/DetailsPage/4906.02005 (Reissue)?OpenDocument

6 Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2016). Australian Burden of Disease Study: impact and causes of illness and death in Australia 2011. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Retrieved March 27, 2018 from https://www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/27216d6d-cd27-46ff-8776-aaf44df97c1f/abod-2011-aus-2017.xls.aspx. Sheet 5: "S13.5: DALY by disease, sex and broad age group, Australia, 2011", Column O ("F 15–44”).

7 National Crime Prevention (2001). Young people and domestic violence : National research on young people's attitudes to and experiences of domestic violence. Barton: Attorney-General's Dept. Retrieved September 21, 2009, from http://www.oneinthree.com.au/ypdv.

8 Smith, A., Agius, P., Dyson, S., Mitchell, A., & Pitts, M. (2003). Secondary students & sexual health. Results of the 3rd national survey of australian secondary students, HIV/AIDS and sexual health 2002 (Monograph series number 47 ed.). Melbourne: Australian Research Centre in Sex, Health & Society, La Trobe University. Retrieved November 8, 2009, from http://webstat.latrobe.edu.au/c.latrobe?nm=http://www.latrobe.edu.au/arcshs/assets/downloads/reports/nat_sch_srvy_02.pdf

9 Australian Bureau of Statistics (2017). 3303.0 - Causes of Death, Australia, 2016. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved March 30, 2018, from http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/DetailsPage/3303.02016?OpenDocument

10 Bryant, W. & Bricknell, S. (2017). Homicide in Australia 2012–13 to 2013–14: National Homicide Monitoring Program report. Canberra: Australian Institute of Criminology. Retrieved March 30, 2018, from https://aic.gov.au/publications/sr/sr002

11 Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2009). Homeless people in SAAP, SAAP national data collection annual report 2007-08. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Retrieved September 21, 2009, from http://www.aihw.gov.au/publications/index.cfm/title/10662

12 Chamberlain, C., & MacKenzie, D. (2003). Australian census analytic program : Counting the homeless 2001. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved September 21, 2009, from http://www.ausstats.abs.gov.au/ausstats/free.nsf/Lookup/5AD852F13620FFDCCA256DE2007D81FE/$File/20500_2001.pdf

13 Commonwealth of Australia (2008). Which way home? A new approach to homelessness. Canberra: Dept. of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs. Retrieved September 21, 2009, from http://www.fahcsia.gov.au/sa/housing/pubs/homelessness/green_paper_homlessess1/Pages/default.aspx

14 Dearden, J., & Jones, W. (2008). Homicide in australia: 2006-07 national homicide monitoring program annual report. Canberra: Australian Institute of Criminology. Retrieved September 21, 2009, from https://www.aic.gov.au/publications/mr/mr1

15 Wolcott, I., & Hughes, J. (1999). Towards understanding the reasons for divorce. Australian Institute of Family Studies, Working Paper, 20. Retrieved November 1, 2009, from http://www.aifs.gov.au/institute/pubs/wolcott6.html

16 Statistics Canada (2008). Family Violence in Canada: A Statistical Profile 2008, Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice Statistics, Ministry of Industry, Ottowa. http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/85-224-x/85-224-x2008000- eng.pdf

17 Romito, P and Grassi, M. (2007). ‘Does violence affect one gender more than the other? The mental health impact of violence among male and female university students’, Social Science & Medicine, Vol 65, pp.1222 –1234.

18 Prospero, M. (2007). ‘Mental health symptoms among female and male victims of partner violence’, American Journal of Men's Health, Vol 1, pp. 269-277.

19 People, J. (2005). Trends and patterns in domestic violence assaults. Crime and Justice Bulletin, 89. Retrieved September 21, 2009, from http://www.bocsar.nsw.gov.au/lawlink/bocsar/ll_bocsar.nsf/pages/bocsar_mr_cjb89

20 Mouzos, J., & Makkai, T. (2004). Women's experiences of male violence: Findings from the australian component of the international violence against women survey (IVAWS). Canberra: Australian Institute of Criminology. Retrieved September 21, 2009, from http://www.aic.gov.au/publications/current%20series/rpp/41-60/rpp56.aspx

21 Indermaur, D. (2001). Young australians and domestic violence. Trends and Issues in Crime and Criminal Justice, 195. Retrieved September 21, 2009, from http://www.aic.gov.au/publications/current%20series/tandi/181-200/tandi195.aspx

22 Dal Grande, E., Woollacott, T., Taylor, A., Starr, G., Anastassiadis, K., Ben-Tovim, D., et al. (2001). Interpersonal violence and abuse survey, september 1999 . Adelaide: Epidemiology Branch, Dept. of Human Services. Retrieved September 21, 2009, from http://www.health.sa.gov.au/pros/portals/0/interpersonal-violence-survey.pdf

23 NSW Parliament (2006). Impact of the Family Law Amendment (Shared Parental Responsibility) Act 2006 (Cth), Standing Committee on Law and Justice, NSW Parliament, Sydney. http://www.parliament.nsw.gov.au/prod/PARLMENT/committee.nsf/0/b22b4bc31d2d2042ca257234000956c6/$F ILE/Impact%20of%20Family%20Law%20Amendment%20(Shared%20Parental%20Responsibility)%20Act%20Cth %202006%20Report%2033.pdf

24 Hume, M. (2006). National Abuse Free Contact Campaign’s response to the Committee’s Inquiry into the impact of the Family Law Amendment (Shared Parental Responsibility) Act 2006 (Cth), Submission 11. http://www.parliament.nsw.gov.au/prod/PARLMENT/committee.nsf/0/1efcba2c54066174ca257212000d2629/$FI LE/ATTYB5GX/sub%2011.pdf

25 The National Council to Reduce Violence against Women and their Children (2009). The cost of violence against women and their children. Canberra: Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs. Retrieved September 21, 2009, from http://www.fahcsia.gov.au/sa/women/pubs/violence/np_time_for_action/economic_costs/Pages/default.aspx

26 See the overview of recent family violence research findings

27 Dearden, J (2009) Homicide in Australia: 2006-07 National Homicide Monitoring Program annual report, email to Greg Andresen (approved for public circulation) 22 January 2009. See http://www.menshealthaustralia.net/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=556&Itemid=79

28 United Nations (1966) International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.

29 Nathanson, P and Young, K R (2001). Spreading Misandry: The Teaching of Contempt for Men in Popular Culture. Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press. Also Macnamara, J R (2006). Media And Male Identity: The Making And Remaking Of Men. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

30 Straus, M. A. (2008). Dominance and symmetry in partner violence by male and female university students in 32 nations. Children and Youth Services Review, 30, 252-275. Retrieved November 7, 2009, from http://pubpages.unh.edu/~mas2/ID41-PR41-Dominance-symmetry-In-Press-07.pdf

31 See http://www.menshealthaustralia.net/files/access_economics.pdf

32 Heenan, M., Astbury, J., Vos, T., Magnus, A., Piers, L. S., Walker, L., et al. (2004). The health costs of violence. Measuring the burden of disease caused by intimate partner violence. A summary of findings. Carlton South: Victorian Health Promotion Foundation. Retrieved September 21, 2009, from https://www.vichealth.vic.gov.au/media-and-resources/publications/the-health-costs-of-violence

33 Taylor, N. & Mouzos, J. (2006). Two steps forward, one step back: Community attitudes to violence against women. Melbourne: VicHealth. Retrieved August 20, 2010, from http://www.vichealth.vic.gov.au/~/media/ProgramsandProjects/MentalHealthandWellBeing/DiscriminationandViolence/ViolenceAgainstWomen/CAS_TwoSteps_FINAL.ashx

34 Vos, T., Astbury, J., Piers, L. S., Magnus, A., Heenan, M., Stanley, L., et al. (2006). Measuring the impact of intimate partner violence on the health of women in victoria, australia. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 84(9), 739-44. Retrieved September 21, 2009, from http://www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/84/9/06-030411ab/en/index.html

35 Tilbrook, E., Allan, A., & Dear, G. (2010, May 26). Intimate partner abuse of men. East Perth: Men's Advisory Network. Retrieved May 26, 2010, from http://www.man.org.au/Portals/0/docs/Intimate%20Partner%20Abuse%20of%20Men%20Report.pdf

36 Queensland Police Service (2009). Annual Statistical Review 2008–09. Brisbane: Queensland Police Service. Retrieved August 20, 2010, from http://www.police.qld.gov.au/Resources/Internet/services/reportsPublications/statisticalReview/0809/documents/AnnualReport_2008_2009.pdf

37 Australian Bureau of Statistics (2011). Crime Victimisation, Australia 4530.0. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved August 8, 2011, from http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/subscriber.nsf/log?openagent&45300_2009_10.pdf&4530.0&Publication&96D24600F95E026ACA257839000E060C&&2009%9610&17.02.2011&Latest

38 Victorian Health Promotion Foundation (VicHealth) (2010, March). National survey on community attitudes to violence against women 2009. Carlton: Victorian Health Promotion Foundation (VicHealth). Retrieved September 20, 2010, from http://www.vichealth.vic.gov.au/~/media/ResourceCentre/PublicationsandResources/NCAS_CommunityAttitudes_report_2010.ashx

39 J Hickey and S Cumines, Apprehended Violence Orders: A Survey of Magistrates, Judicial Commission of New South Wales, Sydney, 1999, p 37

40 B Carpenter, S Currie and R Field, 'Domestic Violence: Views of Queensland Magistrates' (2001) 3 Nuance 17 at 21

41 Parkinson, P, Cashmore J and Webster A, "The Views of Family Lawyers on Apprehended Violence Orders after Parental Separation" (2010) 24 Australian Journal of Family Law 313

42 Parkinson P, Cashmore J and Single J, 'Post‐Separation Conflict and the Use of Family Violence Orders', Sydney Law Review (2011, in press)

43 Kaspiew, R., Gray, M., Weston, R., Moloney, L., Hand, K., & Qu, L. (2009, December). Evaluation of the 2006 family law reforms. Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies. Retrieved July 5, 2010, from http://www.aifs.gov.au/institute/pubs/fle/evaluationreport.pdf

44 See One in Three Fact Sheet 4.

45 See One in Three Fact Sheet 3.

46 Webster, K. (2016). A preventable burden: Measuring and addressing the prevalence and health impacts of intimate partner violence in Australian women (ANROWS Compass, 07/2016), p19. Sydney: ANROWS. Retrieved March 30, 2018, from http://anrows.org.au/file/1828/download?token=150_MEYN

47 Begg, S., Vos, T., Barker, B., Stevenson, C., Stanley, L., & Lopez, A. D. (2007). The burden of disease and injury in australia 2003. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Retrieved September 21, 2009, from http://www.aihw.gov.au/publications/index.cfm/title/10317

48 World Health Organisation (2006). Table 1: Numbers and rates of registered deaths. Australia - 2003. World Health Organisation mortality data-base [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organisation. Retrieved September 20, 2009, from http://www.who.int/healthinfo/morttables/en/

49 Mouzos, J. (2005). Homicide in Australia: 2003-2004 National Homicide Monitoring Program (NHMP) Annual Report. Canberra: Australian Institute of Criminology. Retrieved September 21, 2009, from http://www.aic.gov.au/en/publications/current series/rpp/61-80/rpp66.aspx